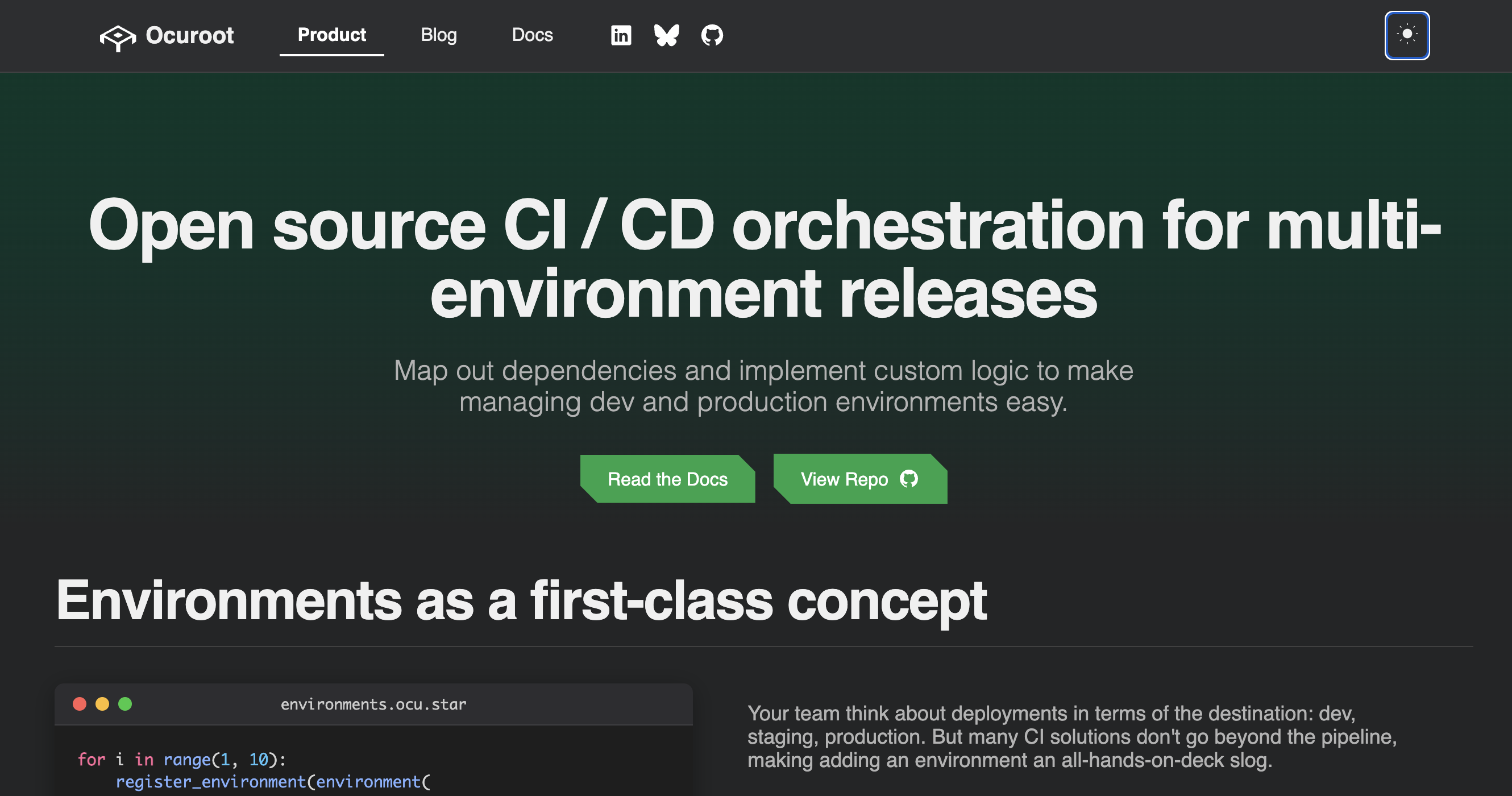

The landing site at www.ocuroot.com recently had a mini-relaunch, which included simplified content, all-new docs and dark mode! But what's most interesting it what's under the hood, with assets generated with Go (and Templ), hosted on Cloudflare and deployed using Ocuroot!

The Why

Earlier versions of the site were built with Next.js, chosen largely because of it's popularity. This led to a lot of context switching between JavaScript and Go. Not impossible to handle, but it added just enough friction to make it less likely for me to make site updates.

The split between the site and the Ocuroot UI was also causing a lot of duplication. Components had to be created in both React and Templ, creating just enough extra work to be annoying, and making it harder to be consistent.

So by moving to building the site using Go, I'd be able to cut down on duplicated work, reduce friction when switching between tasks, and create a little fodder for a blog post!

The How

Templ doesn't have a framework for building static sites per-se, but does make it easy to generate static content from components.

With this as a starting point, it was pretty straightforward to set up an interface to register components with paths and output them to a dist directory later:

r.Register("static/logo.svg", StaticComponent(assets.Logo))

r.Register("index.html", site.Index())

r.Register("privacy/index.html", site.PrivacyPolicyPage())

r.Register("contact/index.html", site.ContactPage())

r.Register("404.html", site.NotFoundPage())

Note the StaticComponent type, this is just a convenience wrapper to allow arbitrary byte slices to

be rendered as a component:

type StaticComponent []byte

func (s StaticComponent) Render(ctx context.Context, w io.Writer) error {

_, err := w.Write(s)

return err

}

Once we have paths mapped to components, it's then just a simple loop to render them.

for path, component := range r.Paths {

fullPath := filepath.Join(outputDir, path)

f, err := os.Create(fullPath)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer f.Close()

err = component.Render(ctx, f)

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

Page content from components is all well and good, but where was I going to keep the CSS for each component? A lot of my components lived in their own packages, and I didnt' want to have to enumerate them all to build a shared CSS file.

Go embeds came to the rescue here. Each component has an embed.go file that registers the embedded css and js files with centralized packages. Resulting in simple files like this example for the navigation bar.

package navbar

import (

_ "embed"

"github.com/ocuroot/ui/css"

"github.com/ocuroot/ui/js"

)

//go:embed navbar.css

var CSS []byte

//go:embed navbar.js

var JS []byte

func init() {

css.Default().Add(CSS)

js.Default().Add(JS)

}

This way, any component I used in a UI would automatically be included in common css and js files. Then the concatenated files could be rendered like other pages:

r.Register(css.Default().GetVersionedURL(), AsComponent(css.Default().GetCombined()))

The call to GetVersionedURL() here returns a path based on a hash of the file contents, for the sake of cache busting.

That made it simple enough to add new content, but I already had a bunch of markdown files for blog posts. For these, I used goldmark to convert markdown to HTML, and chroma for syntax highlighting. I won't go too far into the details, but shout out to the Extensions feature of Goldmark, which made it possible to inject some of my more complex Templ components into doc pages.

I'd written on my personal blog about local testing with Tilt and hosting static sites on Cloudflare, and both of these came into play here. One nice little bonus is that Cloudflare's Wrangler tool has a dev mode, so I could view the content exactly as it would appear on the web. This also meant that my site generation code didn't need to include a local HTTP server.

When it came to deploying the site, I would have been remiss not to use Ocuroot! While it was a pretty simple process, I wanted to be able to deploy to a staging site for sharing with friends for feedback, and manually promote to production.

The result was a simple (~60 line) Ocuroot config (release.ocu.star), and a command-line workflow that looked something like this:

# Build the site and upload to staging

ocuroot release new release.ocu.star

# ... Pause for feedback on staging site ...

# Approve deploy to production

ocuroot state set release.ocu.star/+r11/custom/approval 1

# Execute work to deploy to production

ocuroot work any

An AI Irony

I've found that AI dev tools have been generally good at frontend work (even using nonstandard tools like Templ). But they also have a habit of reinventing the wheel a lot. Existing CSS classes and components are often ignored in favor of creating totally new code. A great way to end up with a messy, difficult to follow codebase.

Oddly, though, while wading through all the excess code, I realized that CSS isn't actually that difficult. In the past, I'd seen CSS as being esoteric and hard to work with, so I tended to shy away from writing it myself in favor of pre-canned CSS libraries. But as I saw what the AI was doing, I started to get comfortable with reading CSS, and even improving it a bit.

So I ditched the libraries, and started writing my own CSS - with occasional help from the AI. Granted, there are some Tailwind class names still dangling around in there, but the cleanup continues!

So believe it or not, AI actually made me a better developer!

Extra Upsides

The move to Go helped a lot with the original goals, but also game with a few unexpected benefits.

While building out the new documentation, I realized that I could import the Ocuroot client code into the website as a Go module, then I could generate CLI documentation directly from Cobra and pull the SDK stubs as embeds for the SDK section. This does have the downside of locking the documentation to a specific version of the client. But starting this way has inspired me to look at using Ocuroot's dependency model to pass this content around.

Hand-rolling my CSS and JS, besides being fun, has also allowed me to cut down the size of the site.

The HTML for the front page is down to 10KB from about 30. The main CSS file is around 10KB, same as before, but without any minification or cleanup of unused classes. Most significantly, the JS file is now down to 5KB from a total of about 1.5MB before!

Having learned some more trickery with HTML and CSS, I've also replaced some images with client-rendered elements, shaving off a few hundred more KB.

While this may not have a huge impact on the user experience, it feels like a pretty decent outcome.

The new site is live, and open sourced on GitHub!